King Bhumibol of Thailand

Excerpted from "The king never smiles: a biography of Thailand's Bhumibol Adulyadej" By Paul M. Handley, pages 7, and 170-173.

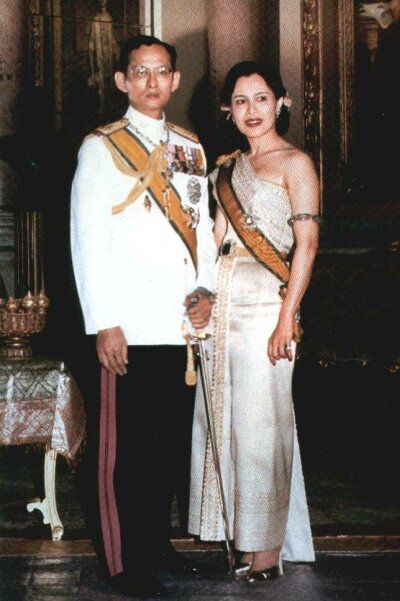

KING BHUMIBOL & QUEEN SIRIKIT

....

Bhumibol is depply adored, often to the point of worship, by the Thai people. This is understandable, as few have heard any doubts about his greatness. In part it is because he is genuinely personable and desirous of helping his people. But this unquestioning adoration also arises from the toughly enforced law of lèse-majesté protecting his inviolateness...

... in 1966 Bhumibol minted a slightly smaller bronze statue, again a sealed Sukhothai-style form, in the position known as Buddha subduing Mara, the representation of evil. It was named Buddha Navarajabophit, or "The Buddha of the Holy Ningth Reign." This suggest Bhumibol as a Buddha-king who repels danger. Although these were stylistic copies of traditional images, the statues were said to incorporate Bhumibol's own personal artistic, and spiritual ideas. The ability to adapt and refine religious icons, like scripture, signaled scaral virtuosity.

Attached to each of these statues was an amulet the size of a silver dollar featuring a seated Buddha image that the king also created in 1965. As a government publication describes it, the king "used a special mixture of auspicious and consecrated materials to make the amulets, "including flowers from garlands the king had placed next to the Emerald Buddha; the king's own hair, trimmed by Brhaman priests; petals from garlands that had hung on the king's umbrulla and sword on the Coronation Day anniversay; dried paint from the king's paintings; and pitch and paint from the king's handmade sailboat. The materials were blended and cast into a small votive tablets by hundreds, which were then handed out to palace favorites and top government and military officials. Recipients were instructed to adhere a piece of gold leaf to the back of the amulets, as well as the large statues, an act of self-abnegating anonymity in merit-making. Only those crudely desiring recognization put gold leaf on the front of an image.

This was to become a key message of the king: to work earnestly without desire for recognition.

The king's amulets rose quickly in appeal and value. They garnered names that reflected the image of the king: the venerable monklike title Luang Pho Chitrlada (The only Holy Father of Chitrlada Palace), and Phra Kamlang Phaendin, the lord who gives trength to the kingdom.

Family life and family image, filled out the roster of activities for Bhumibol in the years up to the mid-1960s. At even more official audiences, charity balls, and social events, he and Sirikit together struck a handsome sight, although she grabbed most of the attention. Vivacious and fashionable, the queen was constant feature in the Thai media, appearing on nearly every women's magazine cover at least once a year.

* * *

On one side she was portrayed as a model wife and a mother, able to cook and clean for her man and her children while looking beautiful in a simple dress, like her modified traditional silk sarong and blouse. At the same time she was the focus of the high society, brightening parties in expensive jewelry and lavish French dresses by Peirre Balman and Madame Carven. On state visits she won the world over, alternating between stylish modern suits, with gloves, hats, and pearls chokers, and luxurious evening gown and furs. She became known as Asia's Jackie Kennedy, and in 1965 she topped the list of world's best dressed woman. The impression the royal couple made was far from frivolous. Thai Buddhist culture peculiarly related frame and beauty to merit, so, elegant and celebrated worldwide, Bhumibol and Sirikit clearly had a great stock of Karma.

Bhumibol was also interested and even doting father to his four children. Palace photographs show the king on the floor with Ubolrat and Vajiralongkorn playing with toy cars, stringing a kite for them, holding and embracing them. Still, Thais leave the job of child reaising almost completely to mothers, aunts, maids, and other women. If Bhumibol hope to give his children some of the normalcy and disicipline of his own upbringing, it was losing battle. With all the indulging caretakers, they could hardly avoid being spoiled. Prince Vajiralongkorn later recited that at 12 he couldn't tie his own shoes, for they were always tied for him.

What the public saw in palace-issued photographs and movies, however, was a dharmaraja king who, besides all his other incredable talents, was a caring, sensitive patriarch of his handsome family. The Mahidols were a metaphor for the nation.

There was one real problem in this picture, theorethically at least. When she was born in 1957, Princess Chulabhorn proved to be the last of the king and queen's children. At 25, Sirikit inexpicably stopped having babies. Four children was a respectable-sized family, but in this case three was only one son, one qualified heir to the Chakri throne.

It left the dynasty at a huge risk. In the six decades since Chulalongkorn had produced his 32nd son, almost all the possible lines of succession had hit dead ends. Prince Varananda Dhavaj, born to celestial Prince Chutadhuj but passed over for the throne in 1925 and again 1935, had married an English woman, disqualifying their two children from succession.

Varananda divorced and later married the King's sister Princess Galyani, a good dynastic strategy, but the couple never had any children. Galyani herself had only one daughter by her own husband a commoner.

Chulalongkorn's son Prince Paripatra left one son, Prince Chumbhotpong or Chumbhot, by his first, royal-blooded wife. Chumbhot however had only one daughter by his royal wife before he died, in 1959. Paripatra's second wife, a commoner also gave him a son, Prince Sukhumbhinanda, who could have been promoted into the line of succession if necessary.

Sukhumbhinanda's wife, though, was also a commoner, leaving their sons, M.R. Sukhumbhand, born in 1953, and M.R. Vararos, born in 1959 as distant options for succession.

The shortage of royal heirs meant that, if Vijiralongkorn died young, the dynasty risked a massive succession crisis involving the numerous ambitious families descended from the Fourth Reign. So it was odd that Bhumibol and Sirikit simply decided that she was tired. Yet it would have been a decision the whole court objected to, though, maybe not the king. Her relatives also would have pressured as the one responsible for the Kitiyakara family's dynastic position.

Another plausible explanation is that physical problems prevented Sirikit from having children again. If so, there were no public revelations. Perhaps, too, the practical-minded Bhumibol himself decided that four children was enough. But, again, there was the unshirkable mission of securing the dynasty. The issue is never discussed, at least in public, but it is crucial. The problem of the King's having only one son would become obvious to all by the early 1970s.

The point raise another question, which is whether Bhumibol ever had other women. His ancestors kept enormous harems, and Thai culture accepted, especially among the elite, men having second and third wives or concubines. A number of men in the King's circle made littke effort to hide their mistresses. Sirikit's father and grandfather, as well as Prince Bhanuband, were all famous for their many women.

It would have been inevitable between jazz numbers and sailing race that talk among the king and his chums turned to women. On the other hand, Bhumibol's uncle King Prajadhipok was a monogamous to a fault, leaving no heirs, and Bhumibol's father was too. In addition, the Swiss environment Bhumibol grew up in frowned on extramarital relations.

Thai traditional accepted that powerful men should have their sexual needs freely gratified. Women offered up themselves or their daughters to enhance their own status. Sometimes a powerful man's wife would herself selects the mistresses, so that she could remain control over her household. Without a doubt, it wasn't long after Bhumibol returned to Thailand before women were offerred to him, attractive and educated women, by their families and by themselves. The Thai royal circle repeats numerous such stories. But how the young king respond is one of the palace's most tightly held secrets. Did he indulge in one of the great fantasies of kingship?

* * *

Some say he had at least one discreet affair over a lengthly time with an unidentified woman from the court circly in 1960s. Others say there were several affairs, though again no names are available. In addition there are two rumors that spreads in 1970s and featured in later Communist Party in Thailand (CPT) propaganda. The first had it that Queen Sirikit gave her own young sister Busba, to the king. Two years younger than Sirikit, Busba was a palace fixture, and in 1957 she remained unmarried. If the rumor was true, it wouldn't have been surprising. Many kings, including Chulalongkorn, made queens of several sisters.

Bhumibol might have done it both for pleasure and for strengten Sirikit's dynastic mission. If Busba bore the king a son, it would have ensured the Kitiyakara family's position in Chakri posperity.

Around the very end of 1957 - five months after Sirikit had her last child- Busba became pregnant with no publicly recognized suitor. Four months into her pregnancy she suddenly married M. I. Thavisan Laddaval, a palace adviser who later became the king's personal private secretary. Their marriage and Busba's giving birth to a daughter in September 1958 made the rumor of Bhumibol's involment moot - neither mother nor child had any impact on the royal succession. He never displayed any paternal attitude toward the girl. Busba and Thavison had no more children and divorced a few years later.

The second story repeated in CPT propaganda was of the king's affair with exceedingly beautiful Thai woman who captured the Miss Universe title in 1965, Apsara Hongsakut. She was said to have been presented to Bhumibol by her father, Air Chief Marshall Harin Hongsakut, or by Queen Sirikit. But the official record doesn't reveal anymore.

Apsara married Sirikit's cousin M.R. Kiartiguna Kitiyakara in 1968, and a year later she gave birth to a boy M. L. Rungkhun. Ever since, Rungkhun has had no obvious connections to the palace. He apparently was sent to study abroad, and not long after returning to Thailand as a teen he disappeared into a monastry. Those who entertain the idea of a Bhumibol-Apsara relationship note the traditional of rival heirs to the throne, like Monkut in 1824, donning a monk's robe for safety.

Ultimately there is no proof that the King ever took a lover outside his marriage to Sirikit. Nothing has ever blemished the public picture of a happily married monogamous royal couple......./

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Related article:

The King Never Smiles